I'm Glad I Exist, 2025 Thesis Show

This work started when I read Wendy Cope's poem "The Orange," describing a hilariously sized orange the speaker shares with her friends, and their newfound appreciation with day to day living. My thesis aims to explore oranges as a soft-spoken yet potent symbol of love throughout history and cultures, and our universal, human tendency to make meaning out of the mundane. My exhibition is a showcase of mixed media illustrations, each based on an aspect of language, tradition, or personal accounts involving oranges that tell another; "I love you. I'm glad I exist.”

"Ju Song," 2025

Based on a Chinese classical poet Qu Yuan’s poem of the same title, which compares human attributes and virtues to an orange tree.

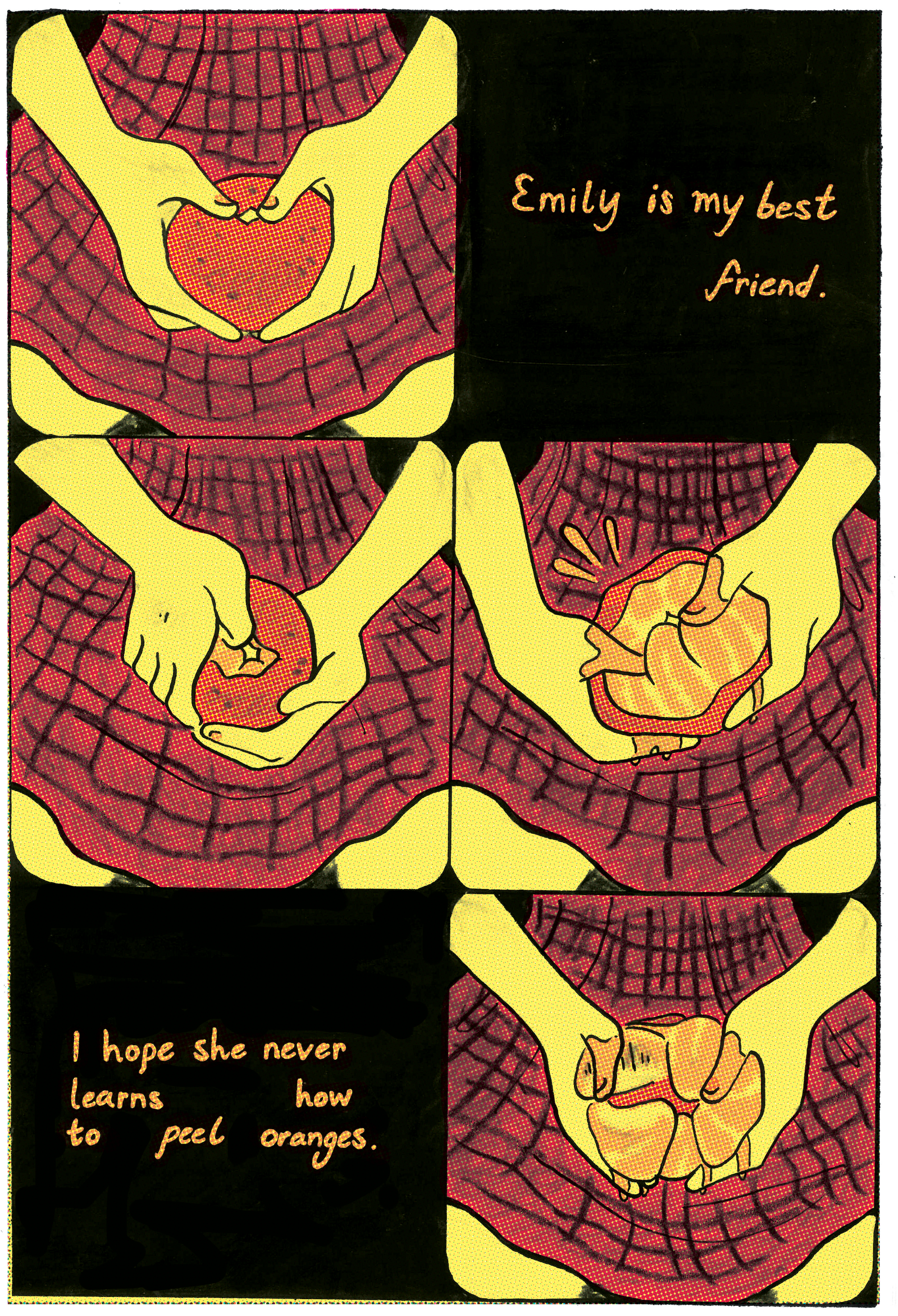

"Emily," 2025

Derived from Jean Little’s poem “Oranges,” that creates a strong, warm intimacy around two girls who share an orange.

"Lovesick," 2024

An homage to Giorgione’s Double Portrait. The orange and its use in early Modern European culture was such a prevalent symbol of unrequited love that several works of visual art and literature cannot be understood without an awareness of this connection.

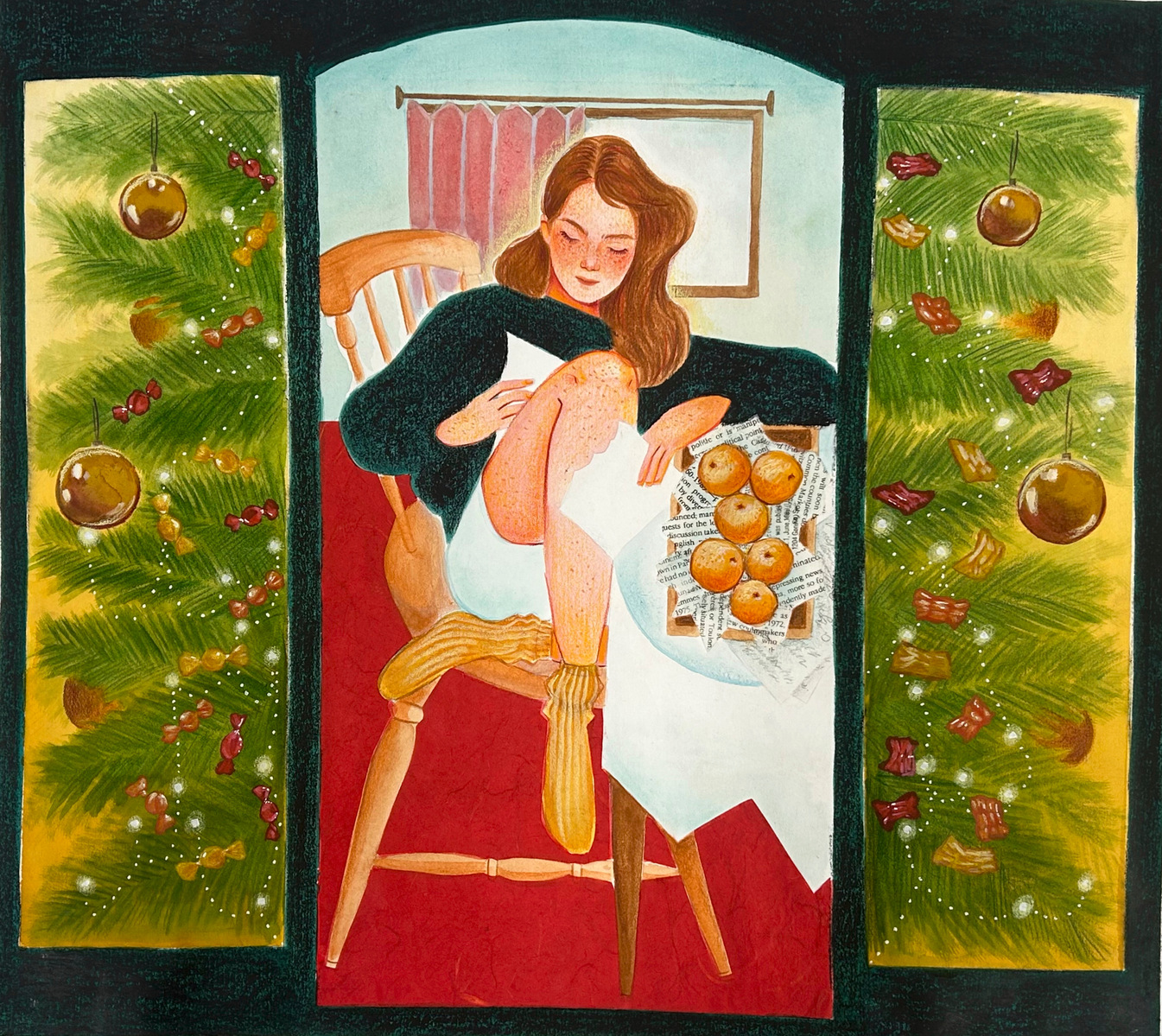

"Pomarancze od Babci," 2025

Portrait of my mother. During Christmas time in Canada, my great-grandmother would send oranges back to her daughter and grandchildren in then Soviet-occupied Poland, where oranges were not available.

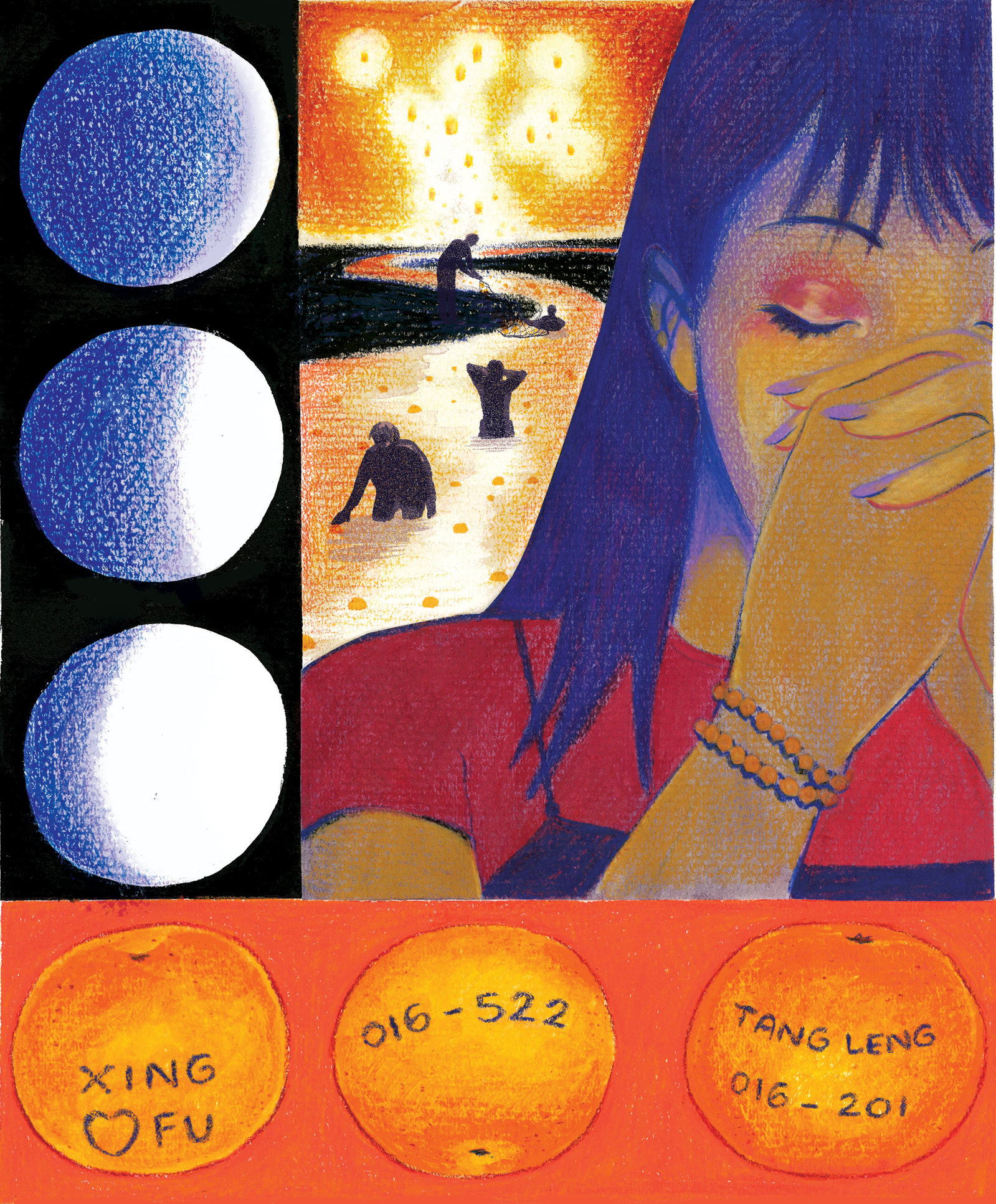

"Chap Goh Mei," 2024

On the fifteenth night during Lunar New Year, Malaysian boys and girls congregate at the Penang river. Girls write their names, numbers, or instagrams on oranges that they then throw into the river for boys to dive into and claim.

"Mi Media Naranja," 2024

An imagined meet-cute in the CMX subway. In Spanish, the idiom for your other half is “mi media naranja,” or literally, “my half orange.”

"Lunar New Year," 2025

Another Lunar New Year festivity includes children of the family gifting their elders mandarins, a symbol of good luck (with its visual association with gold), and love.

"Seder," 2024

The inclusion of an orange on a seder plate is attributed to Susannah Heschel, professor of Jewish studies at Dartmouth College, who included the orange in recognition of queer Jews. In her ritual, each person takes a segment of the orange, and before eating it, says a blessing over the fruit. The seeds are spit out as a rejection of homophobia.